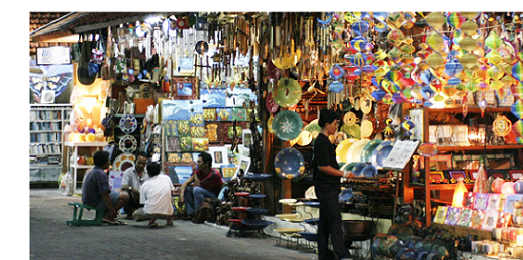

Dozens of micro-entrepreneurs located next to one another, selling a nearly identical assortment of products for identical prices: this is a common sight in cities in low-income countries. Most who have observed this situation have puzzled over it at one time or another, wondering either why the more talented entrepreneurs in the cluster don’t grow larger and push out the less talented, or why the micro-entrepreneurs don’t diversify into different product lines to distinguish themselves from their neighbours. Understanding this phenomenon is crucial for a developing world in which roughly 50% of individuals run a microenterprise as their main economic activity.

A growing recent literature that has attempted to explain the above stylized facts on the basis of firm-level deficiencies or constraints on the one hand, and broad institutional constraints on the other, has found mixed results at best. These explanations include financial constraints (Banerjee et al, 2013; Karlan and Zinman, 2010), human capital constraints (Karlan and Valdivia, 2011) and institutional constraints (de Mel, McKenzie and Woodruff, 2013). In this study, the researchers propose testing the hypothesis that this phenomenon can be significantly explained by social institutions in which groups of microenterprise owners “buy a job” by sharing the demand for particular products or services in their local market. They hypothesize that such institutions are enforced through social pressure (including the threat of physical violence, if necessary), based on anecdotal evidence. Entering into such implicit contracts may be optimal for the participants, by guaranteeing each of them a share of the market and thereby significantly reducing the income volatility that comes about under open competition. However such institutions are likely to yield socially inefficient outcomes: market competition and experimentation are reduced, and the dynamic, compounding benefits of innovation get cut off. If there is heterogeneity in ability, this kind of institution could create an equilibrium in which even the potentially more efficient producers end up running small and inefficient businesses.

The experimental phase of the project will involve a simulated market competition game in which actual micro entrepreneurs will play a game in a lab in which they are given the possibility of using “social pressure” (framed as such in the instructions) to lower their competitors’ output in the context of the game. In the empirical phase of the project, the researchers will use survey data to test for the existence of such social institutions, with the aim of uncovering the mechanisms behind this market friction. They will test for collusive price-setting behaviour in local markets in developing countries using both reduced form and structural techniques. The PEDL grant will in part support the search for a suitable market setting in which the team can exploit natural variation as an exogenous shifter, with the most promising source likely being a supply (i.e. cost) shock. A theoretical model will also be developed to structure the analysis and for welfare implications to be drawn. The framework for this should expand beyond the standard model of collusion (“cartel”) to account for the fact that the group objectives are concerned as much with risk minimization as profit maximization.

This study should raise awareness of this crucial market inefficiency issue among policymakers, which may inhibit firm-level interventions. It should also spur further research to explore ways to help micro-entrepreneurs break out of local market traps.