The word upgrading is used in a variety of ways. This section aims to clarify, conceptually and empirically, how the term has been used and to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of existing empirical measures.

2.1 A Simple Framework

To organize the discussion, some notation and a simple, general framework will be useful. We can think of a firm, indexed by i, as a collection of production lines each producing a single product, indexed by j, using one production technique, k, at time t, characterized by a product-technique-specific production function:

where Yijkt is physical output, Mijkt is a vector of physical inputs (which may include outputs from other production lines in the firm) and λijkt is what Sutton (2007, 2012) and others call the capability of firm i in product-technique jk, which is assumed to raise output conditional on inputs (i.e. ∂Yijkt/∂λijkt > 0). The set of capabilities can also be understood to incorporate what Dessein and Prat (2019) term “organizational capital,” a firm-specific asset that must be produced within the firm and changes slowly over time. A technique can be thought of as a set of instructions for combining particular machines and practices with particular inputs. Let Λit ≡ {λijkt} be the set of capabilities of a firm and let Jit and Kijt be the sets of products and corresponding techniques for which the firm knows Fijk(·).[1] To keep language simple, I will refer to Λit, Jit, and Kijt together as “know-how.”

Suppose that Pijt is the firm’s output price for product j, and that the output demand curves facing the firm are given by Pijt = D(Yijt, Yi,−jt, Zyt ), where Zyt reflects external factors in the output market. Similarly, suppose that the vector Wijkt holds prices for the inputs used in product-technique jk, and that the input supply curves facing the firm are given by Wijkt = S(Mijkt, Mi,−jkt, Zmt), where Zmt reflects external factors in input markets.[2] It is also assumed that the firm faces fixed costs of production, which may be at the level of a product-technique, fijkt, a product, fijt, or the firm, fit, and which may vary across firms (and depend, for instance, on a firm’s capabilities) or across destination markets. It is also asumed that the firm can affect its future capabilities or expand the sets of products and techniques that it knows about by making investments IitΛ , IitJ, and IitK, respectively. A firm’s future know-how may also be affected by the set of products it chooses to produce, or the techniques it uses to produce them.

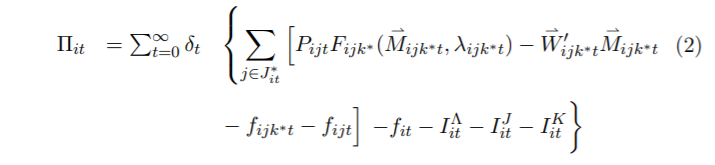

The firm’s present discounted profit can then be written as:

where δt is a discount factor, Jit* is the set of products the firm chooses to produce, and kijt* (indicated by the k* subscript) is the optimal technique chosen for each product, j ∈ Jit*. The firm’s decision problem in any period is to choose Jit*, kijt* for each j ∈ Jit*, the amount of each input used for the chosen product-technique, Mijk*t, and investments in future know-how, IitΛ , IitJ, and IitK, in order to maximize the firm’s present discounted profit, Πit.[3]

In its current form, the framework is too general to be able to generate falsifiable predictions about firm behavior, but it is helpful to define terms and to organize our thinking. The most common definitions of upgrading in the literature can be classified conceptually under four headings, which I will refer to as learning, technology adoption, quality upgrading, and product innovation. These dimensions are related and often occur together but are conceptually distinct.

We can think of learning as an accumulation of know-how: an increase in capabilities, λijkt, for some subset of product-techniques, an expansion of the set of products the firm knows about, Jit, or an expansion of the set of techniques the firm knows about for a given product, Kijt. Implicit in the framework is a distinction between skills that can be purchased on the labor market (and hence show up in Mijkt) and capabilities and knowledge that must be acquired through other means, which may include conscious investments (IitΛ , IitJ, and IitK) or incidental learning from one’s own experience or the experiences of others. Learning would certainly include expansions in Jit or Kijt that also expand the sets of products and techniques available to the world, denoted as Jt and Kjt, but as mentioned above this sort of new-to-the-world innovation (as opposed to new-to-the-firm innovation) is rare in developing countries.

Technology adoption can be thought of simply as the employment of a technique not previously in use by the firm. Here I will use a broad definition of techniques that includes management practices; these are considered to be chosen by firms, given their capabilities.[4] In this framework, production processes are components of techniques, and process innovation can be considered a form of technology adoption. It is tempting to limit the definition of technology adoption to adoption of technologies that are in some sense better than the technologies a firm is currently using. The difficulty here is that technologies are rarely “better” in a global sense - that is, better for all possible levels of know-how and output-demand and input-supply functions. Empirically, it is almost never possible to establish that technologies are globally superior in this way. I will therefore maintain the more agnostic definition of technology adoption as adoption of any technique not previously used by the firm.

Before defining quality upgrading, we need to be clear about what we mean by product quality. It is useful to think about demand functions such as D(·) above as summarizing demands from individual consumers with heterogeneous preference draws (see e.g. Anderson et al. (1992)). A product can be considered to be of higher quality than another in the same product category if it has a higher market share when priced at the same level, although some individuals will be idiosyncratically attached to each product. Quality can be thought of as a one-dimensional index of product attributes that predicts market share conditional on price. In this framework, we can think of output varieties of different qualities (within a product category) as simply being different products, with different labels j. Similarly, inputs of different qualities can be thought of as forming part of different techniques.[5]

Quality upgrading can then be defined as an increase in the average quality of goods produced, as reflected in an output-weighted average of the goods in Jit*. A firm can upgrade in this way without producing goods new to the firm, by shifting output toward higher-quality products already being produced.[6]

Product innovation can be thought of as the production of a good not previously produced by a firm. Product innovation does not necessarily involve learning as defined above, since a firm may start producing a product that is already in the set of products it knows about, Jit, that it happened not to produce before. Product innovation is also distinct from quality upgrading, since the new products may or may not be of higher quality than the products already being produced. Product innovation may entail the switch of a firm to a new sector (given the common practice of assigning firms to the sectors in which they have a plurality of their sales) but most cases do not involve such sectoral shifts.

This framework motivates the categorization of drivers of upgrading in Section 3 below. One set of drivers has to do with conditions in output markets, here summarized by the demand curves, D(Yijt, Yi,−jt, Zty). Another set of drivers has to do with conditions in input markets, here summarized by the input-supply curves, S(Mijkt, Mi,−jkt, Zmt). A third set has to do with the know-how of firms, here summarized by Λit, Jit and Kijt. The demarcation between categories is not sharp. For instance, firms’ capabilities may shape their decisions about which output markets to enter and which sets of consumers to face. Similarly, output or input market conditions, by influencing which products firms produce and which techniques they use, may affect how quickly firms learn. But the categorization seems to be a reasonable way to organize existing studies.

In addition to helping to define terms, this framework highlights three key conceptual points. First, the conditions facing entrepreneurs in developing countries typically differ in a number of ways from those facing firms in developed countries. Developing-country firms often face different (typically poorer) consumers and different prices in input markets, and they have different levels of know-how. These factors influence firms’ choices of which products to produce and which techniques to use.

Second, the four dimensions of upgrading, as we have defined them, are not necessarily optimal for firms or beneficial for aggregate economic performance. More know-how is a good thing for firms, but if acquiring know-how is costly, a firm must weigh the required investment against the future benefits of learning. Whether producing new and/or higher-quality products, or using new techniques, is optimal will depend on conditions in output and input markets and a firm’s level of know-how. When seeking to interpret upgrading behavior, or lack thereof, researchers need to keep in mind the heterogeneous constraints and opportunities faced by firms.[7]

Third, understood through the lens of this framework, the popular conception of “management” reflects three related but conceptually distinct elements: entrepreneurial ability, which we can think of as a component of capabilities, λijkt, that is common across products and techniques and embodied in an entrepreneur; the skill of employed managers, which can be thought of as a component of the input vectors, Mijkt; and the management practices chosen by the firm, which are components of the selected techniques, kijt*. In this view, it is not sufficient to attribute poor firm performance to “bad management”; one needs specify how each of these three elements play a role in the poor outcomes.[8] We will return to these issues in Section 3.3 below.

[1] To keep things simple, I assume that a firm either knows Fijk(·) or not, i.e. that there is no partial knowledge of techniques. In reality, a firm might have uncertainty about Fijk(·) and reductions in such uncertainty are an important component of learning. See e.g. Foster and Rosenzweig (2010).

[2] Again, to keep things simple, I assme that the firm knows the demand and supply functions, D(·) and S(·), but in reality a firm may have imperfect knowledge and may invest in learning about these relationships

[3] There may be adjustment costs involved in changing products or techniques, which can be captured in this framework by the (potentially time-varying) fixed costs fijkt, fijt, and fit. Note that the firm does not necessarily optimize on each production-line independently; for various reasons, including capacity constraints because of fixed factors such as entrepreneurial attention, choices on one line are likely to affect choices on others.

[4] In treating management practices as technologies, I am following, among others, Van Reenen (2011), who argues that the choice of management practices should be analyzed as one would analyze any other technology choice, and Bloom et al. (2011), who write, “Modern management is a technology that diffuses slowly between firms.” See also Bloom et al. (2017).

[5] That is, production processes that use the same sets of machines or practices but different qualities of inputs would be considered different techniques.

[6] A reasonable alternative definition of quality upgrading would be an increase in the highest quality product produced by a firm. As a practical matter, average quality and maximum quality are likely to be highly correlated.

[7] As Foster and Rosenzweig (2010) write in an agricultural context, “it cannot be inferred from the observation that farmers using high levels of fertilizer earn substantially higher profits than farmers who use little fertilizer that more farmers should use more fertilizer” (p. 399).

[8] There may of course be interactions between these elements: for instance, low-ability entrepreneurs may choose low-skill managers, who in turn choose sub-optimal management practices.