A conundrum presents itself in the SEZ policy picture. The main purpose of SEZs is to overcome many of the binding constraints for economic development that are particularly acute in low-income countries, such as those in Sub-Saharan Africa. As a result, the programs offer great hope for these troubled economies. At the same time, the problems in these same countries - poor governance, lack of resources and weak implementation capacity – make the risk of starting and running an SEZ program much higher in these economies than in middle-income countries.

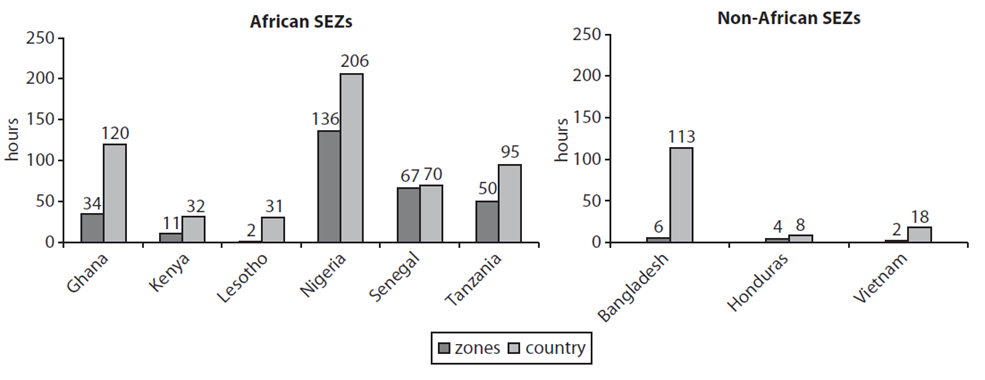

Figure 1. Average monthly downtime due to power outages

Source: Farole (2011)

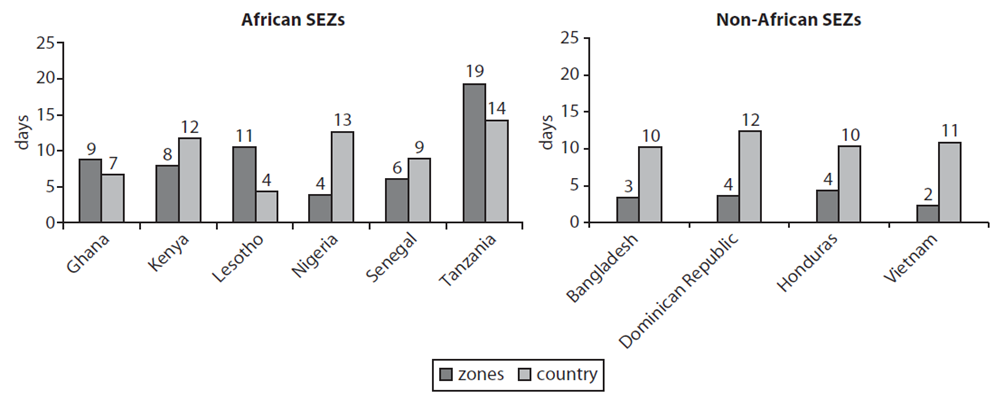

A World Bank study (Farole, 2011) of six African zone programs (Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Nigeria, Senegal, and Tanzania) in comparison with four non-African countries (the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Vietnam, and Bangladesh) and other studies show that success in African zones is limited to a few countries with relatively better performance, such as Kenya and Ghana in the World Bank study and other well known cases such as Mauritius. In terms of investments, exports and employment generation, the African zones are in general falling behind their peers in other continents. One important reason could be the weak business environment (Farole, 2011). Figure 1 shows that the downtime (measured by hours) due to power shortages is still quite high in absolute terms in most African zones – even though the power loss is less severe within the zones themselves than elsewhere in the host African nations. On average, compared with outside zone situations, the power downtime is about 54 percent lower in African zones vs. 92 percent lower in non-African zones. Figure 2 shows that the average time needed for customs clearance is not significantly reduced in most African zones, and in some cases, it actully takes longer within the zones than outside of them. This stands in sharp contrast to the situation in non-African host countries, where the business environment is much better within the zones than outside.

Figure 2. Average time needed for imports through major seaport to customs clearance (days)

Source: Farole (2011)

When assessing the African zone programs, it is important to consider that most African countries are relatively newcomers in implementing modern zone programs, and many of these zones are still in the early stages (Farole, 2011). Changes in and the rebalancing of the global value chain and industrial structures may provide these zones with new opportunities to improve and grow.

Overall, various evidence shows that so far very few African zones (with the exception of Mauritius) appear to have made significant progress toward taking advantage of the dynamic potential of economic zones as an instrument of sustainable structural transformation. Some of the key challenges, among others, include (Zeng, 2015a):

- Problematic legal, regulatory and institutional frameworks. In many African countries, the current legal, regulatory and institutional frameworks for SEZs are either outdated or do not exist - even after the SEZ initiative’s launch, or, in some cases, after the parks have become operational. This “putting the cart in front of horse,” approach has created a lot of confusion, and has deterred potential investors. A review of six zones in Nigeria (Zeng, 2012a; 2012b) underlines the prevalence of these issues.

- Poor business environment. In most Sub-Saharan African countries, the costs of doing business are high. The overall environment is constraining in terms of registration, licensing, taxation, trade logistics, customs clearance, foreign exchange, and service delivery. Many one-stop-shops for investors do not live up to their names.

- A lack of strategic planning and a failure to adopt a demand-driven approach. International experience shows that effective zone programs are an integral part of the overall national, regional or municipal development strategy. Successful zones, such as those in Malaysia, China, the Republic of Korea, and Mauritius build on strong demand from business sectors. In contrast, many zone initiatives in Africa are driven by political agendas, and they lack a strong business case.

- Inadequate infrastructure. This is an overall constraint for all the zones but at different degrees. In general, power, gas, roads, ports, and telecom are the key constraints. Many governments and developers try to use the PPP approach to address these constraints. Given the large investments required for the zones, a strong commitment from government and active participation of the private sector are crucial.

- A lack of operational know-how for zone management. Most of the zone developers, including the relevant government agencies, do not have experience in zone management and operations. Many zone developers are companies specialized solely in construction. Therefore, it is a challenge for them to identify partners that can provide the critical knowledge and expertise on zone management and operations. This lack of expertise seriously undermines implementation capacity.

- A lack of policy consistency, and a failure of host governments to maintain commitments to zones. Zones face uncertainty and difficulty when they must deal with a new government that either does not fully recognize the potential of the economic zone, or does not fully acknowledge commitments made by previous governments. Strong and long-term government commitment is crucial for the success of the zones.

- A failure to address land acquisition and resettlement issues. In some zones, governments’ promises to provide compensation in the case of land acquisition and resettlement were not met or only partially fulfilled. These situations hinder the further development of the zones.

Given the various challenges that the SEZ programs in Africa and other low-income countries face, Africa needs a new SEZ strategy. Such a strategy can draw on the useful lessons and experiences of successful countries, and can build on the following (Zeng, 2015a; 2015b):

- Using SEZs to address the market failures or binding constraints that cannot be addressed through other options. Such constraints may include issues related to land, infrastructure, trade logistics, etc. If the constraints can be addressed through country-wide reforms, sector-wide incentives, or universal approaches, then an SEZ might not be necessary. The experiences of China of using SEZ as a pilot for reform is worth noting. China leveraged the SEZ as a breakthrough towards a market-oriented growth model in an overall very constraining environment and achieved transformative impact. In an extreme environment in the late 1970s and early 1980s (when the planned economy and Cultural Revolution brought China on the verge of collapse), China opened up its economy and offered generous fiscal incentives to lure foreign investors besides good infrastructure and efficient public services. However, today’s macro-environment is different, and many African and other low-income countries in East Asia (such as Vietnam and Cambodia) and South Asia (such as Bangladesh) are the destinations of industrial transfer wave from East Asia. Instead of focusing on tax incentives, governments that want to establish themselves as attractive destinations for investments, should put more effort into enhancing the business environment. Efforts should focus on improving infrastructure, and offering “smart incentives” that encourage skills training, technology transfer/upgrading and local economic linkages.

- Creating a sound legal and regulatory framework and effective institutions with strong and long-term government commitment. In most low-income countries, SEZ laws or regulations are absent or out-of-date, and many investment arrangements are done on an MOU basis. Such practices lack transparency, blur the needed clarity of roles and responsibilities of various parties, and often put investments at great risk. In the Republic of Korea, Malaysia, Jamaica, Jordan and other countries with successful SEZ programs, relevant laws and regulations were put in place when they launched the programs. China formulated the first legislation to govern SEZs at the local level; the SEZ Act for Guangdong Province, passed by the National Congress at the same time as the 1980 launch of the Shenzhen SEZ, includes general and specific provisions on a wide variety of issues (registration and operations, incentives, labor management, etc.). Although the act was drafted by the provincial government, it was enacted by the National Congress to ensure the central government’s full support.

- Fostering a better business environment inside the zone, including efficient services, such as a one-stop shop and good infrastructure. One of the key objectives of the zones is to overcome the constraints (both soft and hard) of doing business in an economy hampered by poor infrastructure, problematic trade logistics, and inefficient, bureaucratic public services. However, in most African zones, these issues remain – even though conditions in most zones are superior to those elsewhere in the African host nations. Power shortages, slow customs, inadequate roads, and unreliable water supplies often make production costs very high. In the successful countries, all basic infrastructure is provided with high quality in most zones and the one-stop-shop services and aftercare are very efficient and effective. Singapore offers a prime example (Box 3). China, Korea, Dubai, and Jordan also make their zones very attractive to investors. Of course, one thing Africa and other low-income countries facing limited resources can do differently from East Asia is that they can attract more private investors through a PPP framework, instead of solely relying on the public funding. Many East Asian countries are also increasingly moving towards this direction.

- Implementing a realistic scheme that starts small. It is crucial to make one or two zones work first before scaling-up. For example, China started with only four zones at very strategic locations, and only rolled out programs in the broader economy after these initial zones (especially the Shenzhen zone) were successful. African and latecomer countries should learn this lesson, start with one or two, and make them truly successful first before taking the program to a larger scale. Many low-income countries start with 10 or even 20 zones all at once; this is a recipe for failure.

- Providing a level of autonomy at the local/zone level coupled with clear objectives, sound benchmarking and monitoring/evaluation. Using SEZs to pilot new reforms, as the East Asian experience shows, would require a certain level of autonomy at the local/zone level. While it is important for the central government to define the overall SEZ strategy/planning and to put in place the right frameworks, the local/zone level should have certain autonomy to test new reforms/approaches to make zones work; in many cases, the specific solutions are on the ground. In Shenzhen, for example, the initial zone had legislative power to pilot reforms to improve the business environment. In Africa and many low-income countries with limited government capacity, the private sector can be effectively leveraged to fill in the gaps in areas of zone management, financing, etc. While zones may enjoy a certain level of flexibility, they also need to be held accountable for the intended results, measured rigorously against the pre-set targets, and benchmarked across different zones.

- Aiding technology transfer, diffusion and skills training. This is crucial for the zones to acquire sufficient manpower, and to make their products competitive. In most African zones, investors struggle to find needed technological support and relevant skilled or semi-skilled workers. Many firms must bring their own technicians/engineers and must conduct training for the local workers – costly undertakings that present a big burden for investors. Most successful zones have well-equipped centers, which work closely with technical and vocational schools, colleges and universities to provide relevant skills training and technological support for the firms in the zones. Some zones also have incubators to nurture new start-ups with seed money. Local governments also have a talent strategy to attract highly skilled people from destinations throughout the world to work in the zones.

- Forging better linkages with local economy. Zones need to build on local comparative advantages and to make local suppliers part of their value chains. In many countries, especially in Africa, zones are often criticized for being “enclaves” without much linkage with the local economy. To fully benefit from the zone programs, governments and zone management need to identify priority sectors, consider local comparative advantages, and help local firms make connections to investors in the zones through supply chains or subcontracting. As mentioned above, in Taiwan (China), and the Republic of Korea, governments encourage the backward linkages through technical assistance and other policy interventions such as duty exemption or tax rebates for local firms that provide inputs or services for the investors within the zones. The Masan Free Zone in the Republic of Korea offers a good example in this regard.

- Practicing sound environmental management. As mentioned before, many successful countries – China, most prominently among them - have paid a high environmental price in the rapid industrialization process. At the early stage, most zones paid less attention to environmental protection in the pursuit of high GDP growth, and today the government is spending billions of dollars to clean up the environmental damage created in its wake. Countries that are only now establishing industrial zones should take this lesson seriously, and adopt strict measures to protect the environment.

- Establishing a good balance between industrial development and social/urban development. Today, zone programs are part of a broad, urban-development agenda. From the zones’ inception, urban master plans should ensure good integration between the zones and cities in terms of infrastructure and social services. Many early-stage zones, especially the EPZs, have not done this very well. Countries launching SEZs should heed this lesson and strike a good balance from the beginning.