.

Today, the concept of the industrial zone is gaining more acceptance globally. Countries across the world are increasingly exploring the possibilities presented by zones, and attempting to seize their potential to catalyze economic development and structural transformation.

SEZs offer a way to create special environments conducive to business in economies where governments otherwise face great difficulties doing so. Governments also use SEZs as a way to attract investments in sectors with no obvious comparative advantage, or as a way of increasing value added in export activities (Cirera & Lakshman, 2014). The basic rationale is that by removing some critical “binding constraints” to economic growth (Rodrik, 2004), SEZ policies create incentives for firms and investors that might not otherwise be attracted. These constraints range from regulatory regimes and infrastructure to land and trade logistics. SEZs are able to overcome these constraints in a controlled environment, and to experiment with some reforms, or new policies and new approaches.

Due to limited resources and implementation capacity, developing countries often cannot create the business environment, or build enabling infrastructure nationwide all at once. In addition, developing countries often have limited political capital to defend policies and reforms against vested-interest groups and political opposition (Zeng, 2015b). This makes targeted interventions or a pilot approach necessary, especially at the initial stages. SEZs are able to create a better business environment in a geographically limited area, through a more liberal legal and regulatory framework, efficient public services, and better infrastructure within the zone, including better roads, power, water, and wastewater treatment. Some newer-generation zones are even becoming the drivers of green development and eco-industrial cities (Zeng, 2015b).

In the economics literature, the views on SEZs are quite mixed, partially because of the mixed results of SEZ programs in different countries or economies, as previously discussed. Quite a few scholars view SEZs as a suboptimal strategy or second- or third-best options for development. Some contend that SEZs benefit a few, and distort resource allocation (Engman et al., 2007). Others believe that the zones’ success is confined to specific conditions over a limited time horizon (Hamada, 1974; Madani, 1999). Some economic research finds that SEZs are welfare reducing (Chen, 1995; Hamada, 1974; Hamilton & Svensson, 1982; Wong, 1986), and other research raises concerns that SEZs may become “enclaves” (Kaplinsky, 1993).

At the same time, other research shows that overall social welfare may be improved under certain conditions, such as by attracting foreign direct investment and through enhancing export diversification (Alder et al., 2013; Jenkins et al., 1998; Miyagiwa, 1986; Wang, 2013). Empirical research shows that many SEZs have attracted foreign direct investment, generated jobs and exports, and demonstrated a marginally positive cost-benefit effect (Chen, 1993; Jayanthakumaran, 2003; Monge-Gonzalez et al., 2005; Warr, 1989; Zeng, 2010; Fuller and Romer, 2012). Examples are quite evident, especially in East Asian experiences.

In addition, the basic economic model for the establishment of SEZs highlights the possibility of spillovers to the local economy. Hamada (1974) notes that there may be externalities or learning effects for the domestic, non-zone-based firms, which may become more efficient after the introduction of foreign investment. SEZs may also affect the welfare and labor markets of the local economy Case studies have highlighted spillover effects associated with the establishment of SEZs (Creskoff & Walkenhorst, 2009). Positive spillover effects can come in the form of enhanced economic productivity, newly available technology, and local social welfare effects on the domestic population (FIAS, 2008; Wang, 2013; Ge, 1990).

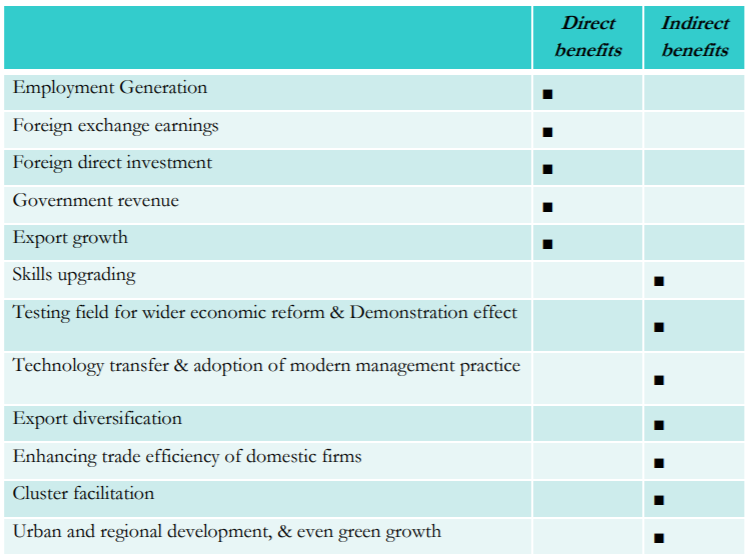

In general, if implemented successfully, SEZs confer two main types of benefits, which in part explain their growth in popularity: “static” or “direct” economic benefits such as employment generation, export growth, government revenues, and foreign exchange earnings; and the more “dynamic” or “indirect” economic benefits such as skills upgrading, technology transfer and innovation, economic diversification, and productivity enhancement of local firms. (Zeng, 2010). Table 2 provides a list of possible benefits from successful SEZ programs. In general, the “indirect” benefits are harder to achieve unless the zones are very successful.

Table 2. Potential benefits of successful SEZ programs

Source: White (2011) and author's research.